|

The graffito on the gaming board from the Red Craig house, Birsay, Orkney |

|||||||

|

This paper concerns a small graffito scratched on the end of a stone gaming board. The board was found in the excavation of a Late Iron Age house at the Red Craig in Birsay, Orkney (Morris 1989). It was originally thought to belong to the Viking period on the basis of parallels with three other boards found nearby, but the subsequent publication of another example from an earlier context at Howe in Stromness suggests that all the boards are likely to be Late Iron Age/Pictish. The suggestion offered here is that such a change in interpretation offers new possibilities for interpreting the graffito and its cultural context.

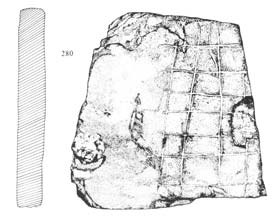

The Red Craig gaming board was originally a stone of portable size with a square grid of seven lines in each direction incised on one face. When found it was broken across with about half remaining (Fig 1). There is a small group of graffiti at the side of the board, consisting of an area of close parallel lines and a small "D" shape. The D-shape has four lines at right-angles to its straight edge each with a small angled mark at the end (Fig 2). The grid and the graffiti are both informal and seem unlikely to have been of lasting significance to the maker or to the players but the D-shaped object has been drawn with care and seems to have been intended to represent something specific (Batey et al, 1989, 220, RF 280; OM BY 280). The find context The gaming board fragment was found in a late occupation phase of a cellular house, apparently deposited at a time when the building was falling out of use and dumps of organic material were accumulating.

The fragment was in one of these dumps, along with 'iron objects, flints and a possible whetstone' (Morris 1989, 156), in a context which the finder recalls as containing very little other stone (Joyce Gray, pers com). The remainder of the board was not found. Possibly the game had been played a long time before the fragment was deposited. The radiocarbon dates for the context in which it was found fall in a broad late Iron Age/Early Viking range (Morris 1989, 171). The architectural style of the Red Craig house belongs to Orkney's pre-Viking building tradition, with parallels from the neighbouring settlement site of Buckquoy (Ritchie 1977) and from the Brough of Birsay (Hunter 1986), but clearly such houses could have remained in use into the Viking period. There is a strong assumption in the concluding discussion of the original report that, though the gaming board was made on-site in Birsay, its cultural connections were with Scandinavia and with the Viking period, in line with the interpretation of the three boards found at Buckquoy (Batey et al 1989, 225). It was tentatively suggested that the D-shaped object might represent the hull of a boat, though if it had four masts it would be " . . . a remarkable depiction for the Early Medieval period, and is quite unlike any remains, or depictions, of contemporary vessels from Scandinavia or the British Isles." (Batey et al, 1989, 220). The Parallels The closest parallels for the Red Craig board are three boards from Anna Ritchie's excavation at Buckquoy and one from Howe in Stromness (Ballin Smith, 1994). Each has a seven-by-seven grid drawn on a portable sized stone, but none has graffiti comparable with that from the Red Craig. The Buckquoy site was only yards from the Red Craig house. Excavation there revealed five phases of domestic buildings, of which the earliest two were cellular and interpreted as 'Pictish' and the later three were rectilinear and interpreted as Viking-period. Of the three gaming boards from the site, one was found in the midden in a barn belonging to the Viking phases. The other two boards were found on the spoil-heap and thus are not stratified, though the excavator thought they were also likely to have come from late phases (Ritchie 1977, 187). Claude Sterckx reported on the Buckquoy boards, identifying them as boards for a 'battle' game of a type found in Scandinavian and Celtic tradition, appearing in Iceland as hnefatafl, in Ireland as brandubh and in Wales as tawlbwrdd (Ritchie 1977, 187). Ritchie believed that the Buckquoy boards were most likely for hnefatafl, saying '…the Buckquoy boards belong to a Norse cultural assemblage…' (ibid, ). However, though the came from a Viking building, the associated artefact assemblage is curious for almost all the finds are either culturally-ambiguous or are Pictish. Almost the only culturally-Viking artefact from the Buckquoy excavation is a broken perforated skewer-pin from Phase 3 (Brundle et al, 2003, 96). Since the assemblage cannot be said to be clearly Norse the cultural affinities of all three Buckquoy boards are unclear. The remaining gaming board is from Howe in Stromness, a site some twelve miles to the south of the others. The board was found in the upper rubble layers of a Middle and Late Iron Age settlement, in a context 'probably from the 6th and 7th centuries and possibly as late as the 9th…' (Ballin Smith 1994, 188). There are few carbon dates from the Howe excavation so the estimate of possible dates for the structures is very broad. However, not only is there no artefactual evidence for Norse occupation on the excavated site at Howe, but the finds assemblage contained little of the fine bone and antler work normally associated with the latter part of the Late Iron Age in Orkney. This suggests that the date of the settlement is likely to be early in the Late Iron Age and to have ended well before the Viking period and that gaming board from Howe is very unlikely to come from a Viking cultural context. Given the culturally-ambiguous find contexts of the boards from Buckquoy and the Red Craig, and the similarity of all five boards to one another, it seems likely that they are all Late Iron Age / Pictish rather than Norse and that the D-shaped graffito originated in that cultural context. The Late Iron Age in Orkney is customarily divided into two by archaeologists with the first part (LIA I) running from about 200-625 AD and the latter part (LIA II) from about 625-800 AD. (e.g., Buteux 1997, 256). There seems to be a sharp transition in material culture between the two periods, with fine pottery and high-quality bone and antler artefacts characterising the latter period. It is the latter period that archaeologists working in Orkney associate most strongly with the Picts. The Picts are one of the peoples of northern Britain, recorded by Eumenius, Adomnan, Bede and many others, but they left no written records of their own. They are best known for their remarkable and enigmatic symbol stones. The distribution of these stones shows that the territory of the Picts extended from Fife to Shetland (Foster 1997, 73). There are some 11 stones from Orkney bearing Pictish symbols or figures (RCAHMS 1989, 36-8) as well as five carved bones. Seen from one side the Red Craig graffito resembles a boat, but turned the other way up it seems like an animal. The four lines with their angled ends become four legs with feet and the D-shape itself becomes the body, with a curved back. Drawings of animals occur both in Pictish and in Viking art. Pictish animals on symbol stones may be drawn with head and tail lowered, producing a curved back line like that on the Red Craig graffito. The closest parallel for a Pictish graffiti animal is a boar incised on a stone from Old Scatness Broch in Shetland (RCAHMS 1999, 42). The Scatness drawing is larger and much more detailed than that from the Red Craig but they are stylistically similar; each drawing has a vigorously-drawn horizontal line forming the underbelly of the animal, with a D-shaped body above the line and the legs below. Taking these similarities with the contextual evidence, it would seem most likely that the Red Craig graffito is a Pictish animal. If the graffito is a tiny Pictish animal, it is part of an intriguing pattern. Pictish symbols and animals occur on a limited range of objects in Scotland, and seem to fall into three broad categories. The first group is the Class 1 stones, ranging from the very 'simple' examples from Pool in Sanday and from the Earl's Bu in Orphir to the magnificent stone from the Broch of Burrian at Garth in Harray. (Ritchie, G., 2003). The stones from Pool and from Burrian were found face-down, as was the eagle-stone from Oxtro, now lost. Elsewhere, Neil Curtis of the Marischal Museum has observed that the carving on stones from Tillytarmont in Aberdeenshire was fresh when they were excavated in the 1950s, but is now deteriorating after only some fifty years. He suggests that it is likely that when they were made they were not exposed for long (Curtis pers com). It would be interesting to know if a significant number of stones had been deliberately placed face-down, or if this small sample is only an erratic statistical cluster. The second group includes the ostentatious objects, including the Class 2 symbol stones which seem to have been intended for display. These have not yet been found in Orkney, though perhaps the Pictish eagle on the Corpus Christi gospel fragment might be included in this group (Henderson, G., 1987, 78). The third group consists largely of graffiti, whether on large areas like the East Wemyss caves (RCAHMS 1999, 24) or on trivial-seeming objects of bone or stone. Among others, these include the stones from Old Scatness in Shetland (Nicholson and Dockrill, 1998) and a stone disc from Jarlshof with a double-disc on one side (Hamilton 1956). There are carved bones found in Orkney at the Broch of Burrian in North Ronaldsay (MacGregor 1974), Pool in Sanday (Hunter 1990, 186-7), the Knowe of Skea in Westray (Graeme Wilson, pers com) and the Bu Sands in Burray (Lawrence 2004). Three of these bones are cattle phalanges, likely to have been gaming pieces. If the grafitto on the Red Craig gaming board is a Pictish animal drawing, it might be part of a pattern linking Pictish graffiti to gaming, but the other Pictish symbol-bone from Pool has no obvious gaming connection, nor does the piece from the Knowe of Skea. One of the Scatness stones was part of the kerb of a hearth, but generally Pictish Art has not been found in domestic settings, on pottery, nor on personal and household artefacts. No sensible interpretation will be possible until there is an inventory of portable Pictish Art like the RCAHMS list of the carved stones.

The first of these groups of Pictish Art may have had spirirtual significance, the second political display or signs of affiliation - or they may not. Given that the surviving household and personal goods of Late Iron Age Orkney are not decorated with symbols, it is tempting to think that the graffiti might have been produced by a special group of people, or in circumstances distinct from daily life, but the evidence is incomplete. Archaeology can only find the more durable Pictish artefacts, and not all of those. There is no record of how wood, leather or cloth may have been decorated, nor of whether the Picts really did paint or tattoo their own bodies as has sometimes been suggested. All that can be said is that enormous amounts of information are must be missing. Given the number of Late Iron Age sites that have been excavated in Orkney over the last thirty years, the wonder is not how many examples of Pictish art we have but rather, how very few. References

|

|||||||